Where does violence begin?

Dysfunctional families as a framework for society

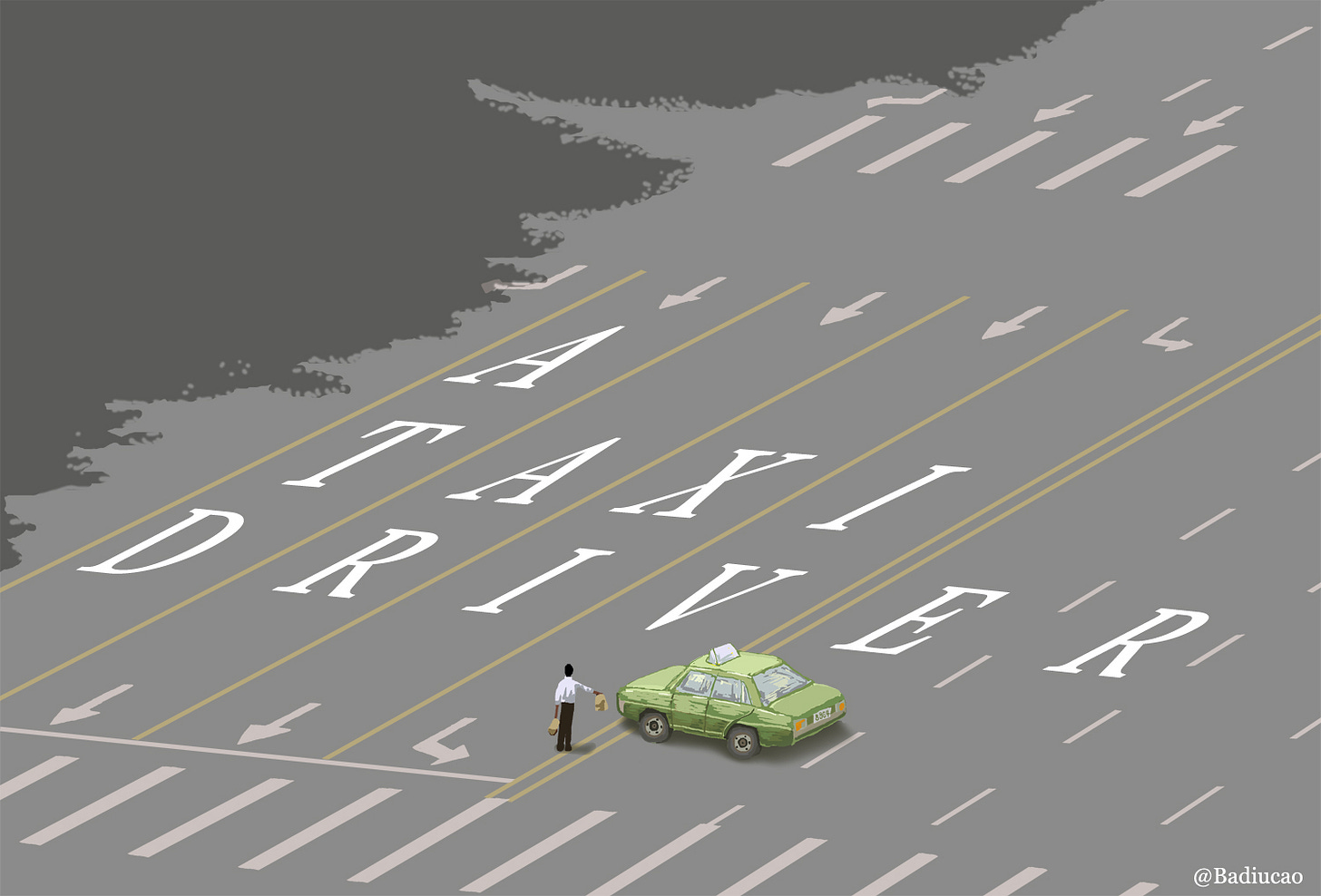

I recently watched Jang Hoon’s film A Taxi Driver, a historical drama based on a true story that depicts the events leading up to and following the Gwangju uprising in 1980. The story follows a taxi driver who is tasked with transporting a foreign reporter in and out of the city where the uprisings take place. The film is worth watching, so I won’t spoil too much in summarizing what happened, but I will say that witnessing everything that happened in the film caused me to internally reflect on the origins of violence, especially in my own life.

To call the film violent is an understatement. It depicts human death and evil acts at the hands of a corrupt government in such a graphic manner, and while the story takes place in an entirely different country from where I live, one with a very different government and society, the parallels felt impossible to ignore.

Who is responsible for teaching us how to be violent?

As humans who all came from families of some sort, I’m thinking of the learned dynamics that come with age and observing others who are responsible for our well being. Everyone needs therapy, but not everyone has access, and more importantly, not everyone sees the benefit of it. I come from a culture and family where therapy has historically been stigmatized in such a way that even the most vague mention of mental health could warrant violence. Never mind the inherent violence that already exists in families prior to even becoming aware of how it has affected one’s mental health.

bell hooks’ All About Love: New Visions, begins with a simple but profound sentiment on punishment and boundary setting within families:

Setting boundaries and teaching children how to set boundaries for themselves prior to misbehavior is an essential part of loving parenting. When parents start out disciplining children by using punishment, this becomes the pattern children respond to. Loving parents work hard to discipline without punishment. This does not mean that they never punish, only that when they do punish, they choose punishments like time-outs or the taking away of privileges. They focus on teaching children how to be self-disciplining and how to take responsibility for their actions. Since the vast majority of us were raised in households where punishment was deemed the primary, if not the only, way to teach discipline, the fact that discipline can be taught without punishment surprises many people.

The rest of the book goes on to discuss several topics related to family dysfunction, violence, and how all of these behaviors happen as a supposed result of “love” inevitably dissecting the definition of love that perpetuates such dysfunctional behavior.

I cant help but wonder who raised the people who find themselves in positions of government and global power. Did those people come from households that were trying their best? Did their parents punish them as an act of love? Were they taught that it was okay to lie, to cheat to get ahead, to step on anyone, and to strive for power? Did their parents see thoughtless punishment as a necessary part of growing up?

hooks continues:

We start out committed to the right path but go in the wrong direction. Most of us learn early on to think of love as a feeling. When we feel deeply drawn to someone, we invest feelings or emotion in them. That process of investment wherein a loved one becomes important to us is called “cathexis”…We all know how often individuals feeling connected to someone through the process of cathecting insist that they love the other person even if they are hurting or neglecting them. Since their feeling is that of cathexis, they insist that what they feel is love… when we understand love as the will to nurture our own and another’s spiritual growth, it becomes clear that we cannot claim to love if we are hurtful and abusive. Love and abuse cannot coexist.

I’m at a point in therapy where I’ve finally begun to understand how useless boundaries are in the face of abuse. It’s impossible to put up boundaries if I’m being abused in any type of relationship. Sometimes, we don’t even know that we’re capable of such abuse, but hooks argues—and I’m inclined to agree—that we are all raised to some degree, in dysfunctional households. That means we are all capable of causing harm and abuse to anyone we encounter. If we don’t call into question the values that we were raised with or the opinions of our families that we’ve adapted as our own, it’s possible to fall into a pattern of self abuse that is then mirrored towards others.

This reminds me of a conversation I recently had with a loved one, someone who has had trouble understanding and connecting with people who are queer. They happen to be religious and adopt certain culturally religious views of queer people, though they are committed to growing and learning how to be more accepting of all people. They said to me, “You know, everything you’re saying about queerness makes sense to me, it’s just difficult for me to understand or accept because it’s not how I was raised.” As if being raised a certain way gives us a pass from evolving to be accepting, loving, and kind adults. I responded by talking about how I was raised in a household that was also homophobic, racist, bigoted, and sexist, and how I refused to see that as a viable excuse for my own behavior as an adult. I have a responsibility to unlearn many of the ideas I was raised with, and the hardest part is that I’m not always aware of what I’ve internalized from childhood. To me, adulthood is about holding myself accountable to the ways I view the world, engage with others, and cause harm. I’m not always successful, I fail often, but I’m trying my best.

State and government violence

I think about the people that make up governments, the people who hold positions of power and are responsible for other people’s ability to live. The first thing I notice is the lack of boundaries and honest communication—thinking of governments that spy on their citizens, that barge into homes, imprisoning and displacing innocent people. I notice how dynamics of interpersonal relationships play out on a global scale—propaganda and the peddling of false narratives to a society is the same as gaslighting within an interpersonal relationship or a work relationship. The killings and beatings of innocent people, directly correlates with a domestic violence dispute where one party holds power over the other. The desire to censor the truth—in the case of A Taxi Driver, to not allow foreign press into the city where the most violence against citizens takes place—feels eerily similar to a family with a parent who is responsible for causing physical and emotional harm to all the members of the family, demanding that “what happens in the family, stays in the family.” The secrets, the dishonesty, the censorship of speech. I’m thinking of Chernobyl, and how desperately the Soviet government sought to cover up the abuse and deaths of its people. What happens in the family, stays in the family. So much that there is a complete denial of the truth, that the number of people who died can’t even be verified because the information was never recorded. And all the other forms of state sanctioned violence that happen every single day, from within the borders of our own country, to occupied Palestine, Afghanistan, Haiti, and countless others.

If every country, state, city is a family, then every family is dysfunctional as all hell.